Published by Alberta Press, a Subsidiary of Walther Koenig and Sharjah Art Foundation

Simian’s Way – He Decided to Walk to Repay the £20, a book consisting almost entirely of cropped images, was published in 2003, a moment overshadowed by the imminent invasion of Iraq by the United States and the United Kingdom (“the Coalition of the Willing”). The work’s title gestures to multiple references: Marcel Proust’s Swann’s Way, the notion of “aping” (simian), and a nod to Simeon Wade, a teacher of Dustin Ericksen’s in graduate school. But at its heart, the project begins with a simple personal obligation: Ericksen, recently arrived in London and facing financial struggles, needed to repay £20 he had borrowed from writer Adrian Searle.

Although Simian’s Way is ostensibly triggered by a mundane debt, Ericksen’s sensitivity to signage owes something to an earlier apprenticeship with master signwriter Phil Yellin, from whom he learned the foundations of typography and layout. This awareness informs the documentary mode—from sleek corporate logos to hastily crafted protest placards—recorded on the walk from Dalston to Shoreditch. By choosing to walk instead of using public transport, the act of repaying Searle became an extended journey that ultimately captured a tightly controlled view from London’s streets. In that view, Simian’s Way reflects the city’s mounting anti-war sentiment, as protest posters clashed with the commercial signage that lined Kingsland Road. In recording every sign, Ericksen created a visual narrative that situates an ordinary moment within the larger context of impending conflict and civic dissent.

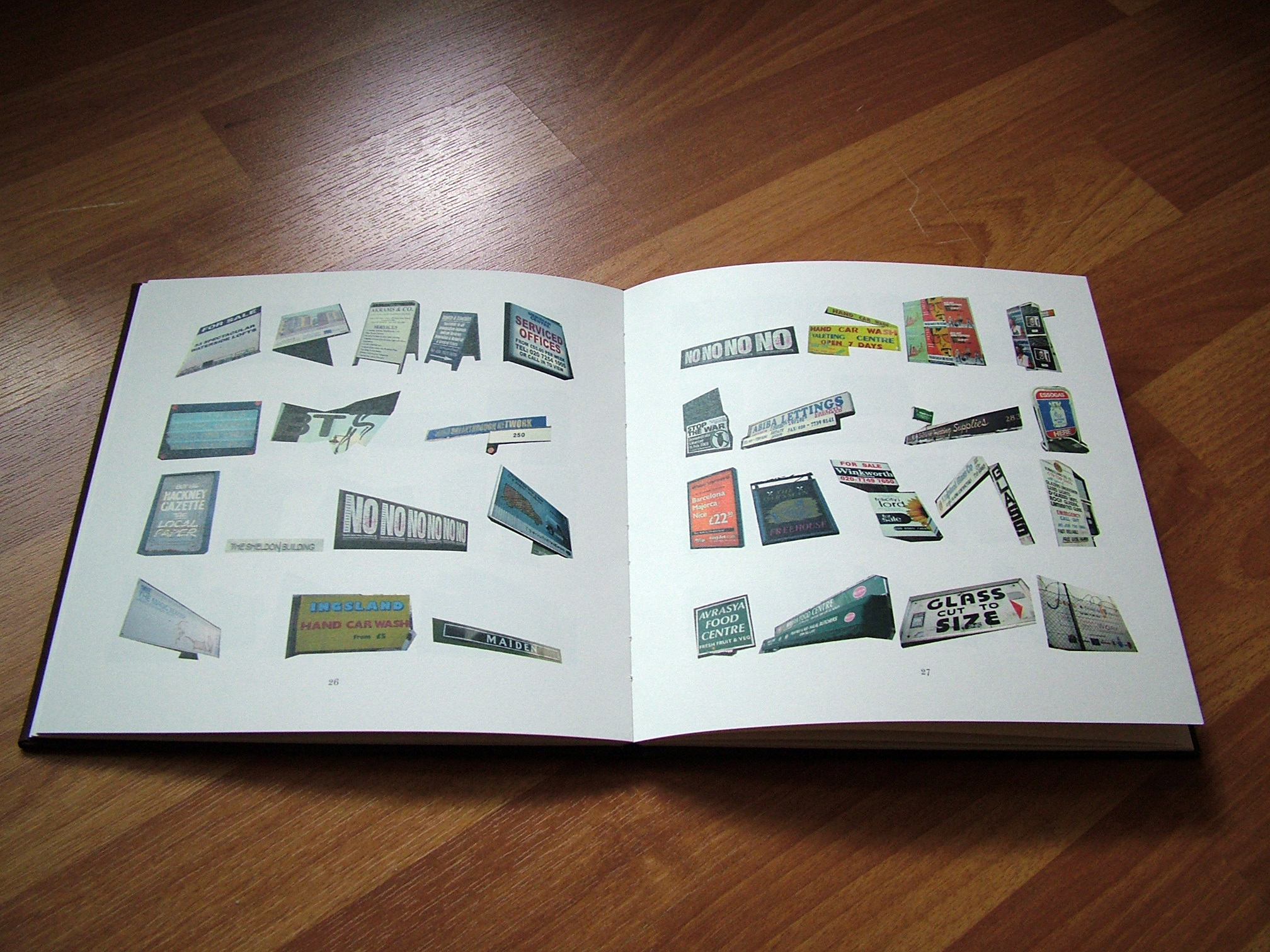

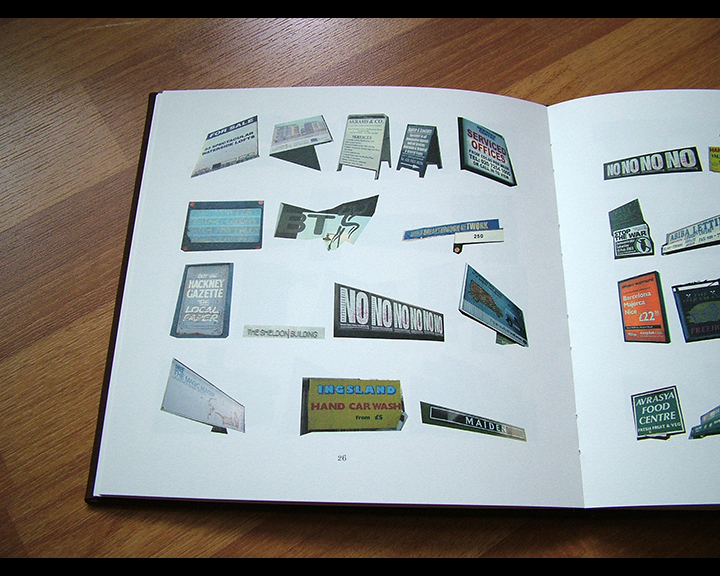

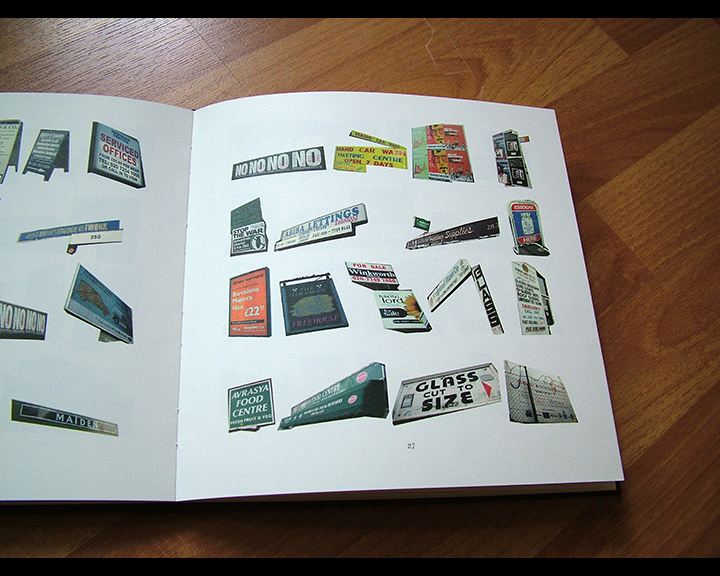

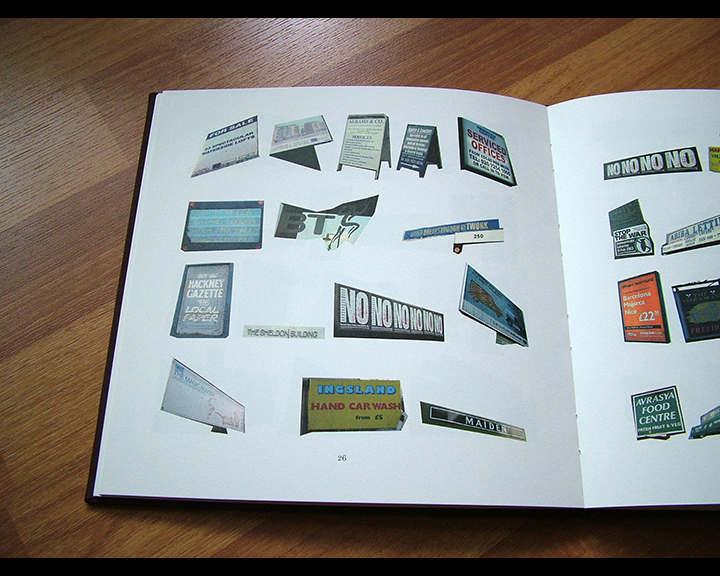

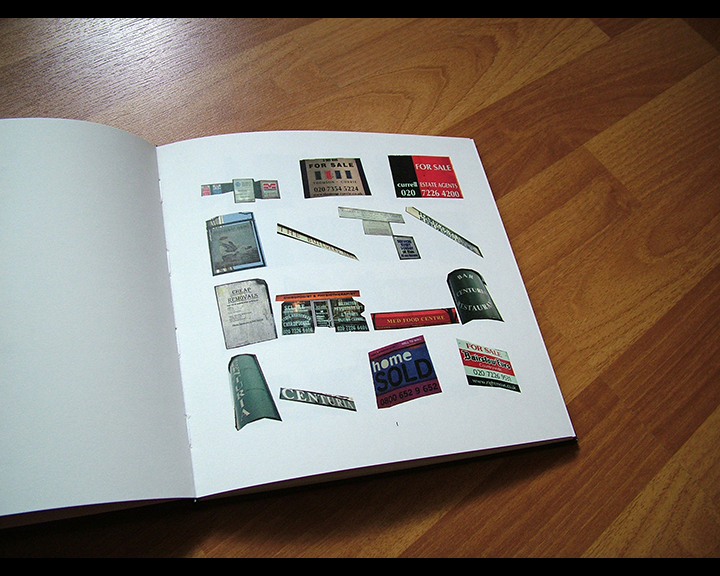

Simian’s Way belongs to a series of walk-based photographic pieces in which Ericksen follows clear constraints: photograph every sign in view, then digitally isolate these signs by cropping out other details. The resulting images appear as discrete elements, odd shapes of anamorphic projection arranged either page by page in book form or compiled into a single composite print. Earlier, in 2001, Ericksen created All the Signs from Raid Projects to Western Exterminator under similar rules, documenting a route in Los Angeles against the backdrop of the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan. He would later produce large-format digital prints—like All The Signs on a Walk to Meet Simon English at The Cheshire Cheese (2005)—on days of major protests, deliberately intersecting his route with demonstrators. These systematic acts turn everyday walks into visual archives that capture both routine surroundings and urgent political messages.

What might have been a strictly private transaction—repaying £20—becomes the generative spark for a socially and politically charged artwork. This conflation of personal economics and public space highlights how individual movements are never entirely isolated; they play out amid broader contexts of political tension, collective anxiety, and urban flux. In Simian’s Way, the seemingly trivial act of returning borrowed money dictates the start and end points of the walk, the route taken, and the precise sequence of signs photographed.

As the artist progressed on foot down Kingsland Road, London’s anti-war fervor intensified around him. Commercial signs—often uniform in branding and typography—stood out against the raw urgency of the protest posters repeating “NO NO NO NO”. By placing these distinct messages side by side in a book format, Simian’s Way reveals how a single path can unite dissonant expressions of consumer culture, civic identity, and grassroots resistance. The passage of time emerges in the shifting light conditions: early photographs appear bright, while later frames darken, chronicling an all-day walk. Arranging the images into “gangs” on each page compresses real distance into a layered visual record, inviting viewers to engage both momentarily (with each sign) and cumulatively (with the entire progression).

Simian’s Way aligns with the concepts of “expanded sculpture” and “expanded painting.” Each isolated sign mirrors a cut-out form, reflecting the skewed vantage of a pedestrian looking upward or sideways. Beyond these aesthetic considerations, Ericksen’s arrangement recontextualizes commercial, local, and protest signage into a new composite. He thereby transforms what might be transient street visuals into a platform for reflecting on urban experience, historical moment, and individual agency.

By casting a personal debt repayment as the organizing principle of a socio-political art document, Simian’s Way illuminates how the private inevitably intersects with the public. Ericksen’s methodical cataloging of every sign—across corporate, vernacular, and activist spheres—underscores that no singular movement occurs in a vacuum. City streets become theaters of economic transactions, collective anxieties and a competition of aesthetic priorities. In this regard, Simian’s Way is a time-based, politically charged artwork that subtly captures an urban milieu on the brink of war.

Quint Vantage

2005